Shopping Cart (0)

Your cart is currently empty.

TRIPLET30: 30% off on purchase of 3 books

Your cart is currently empty.

-By Deepshikha Pasupunuri

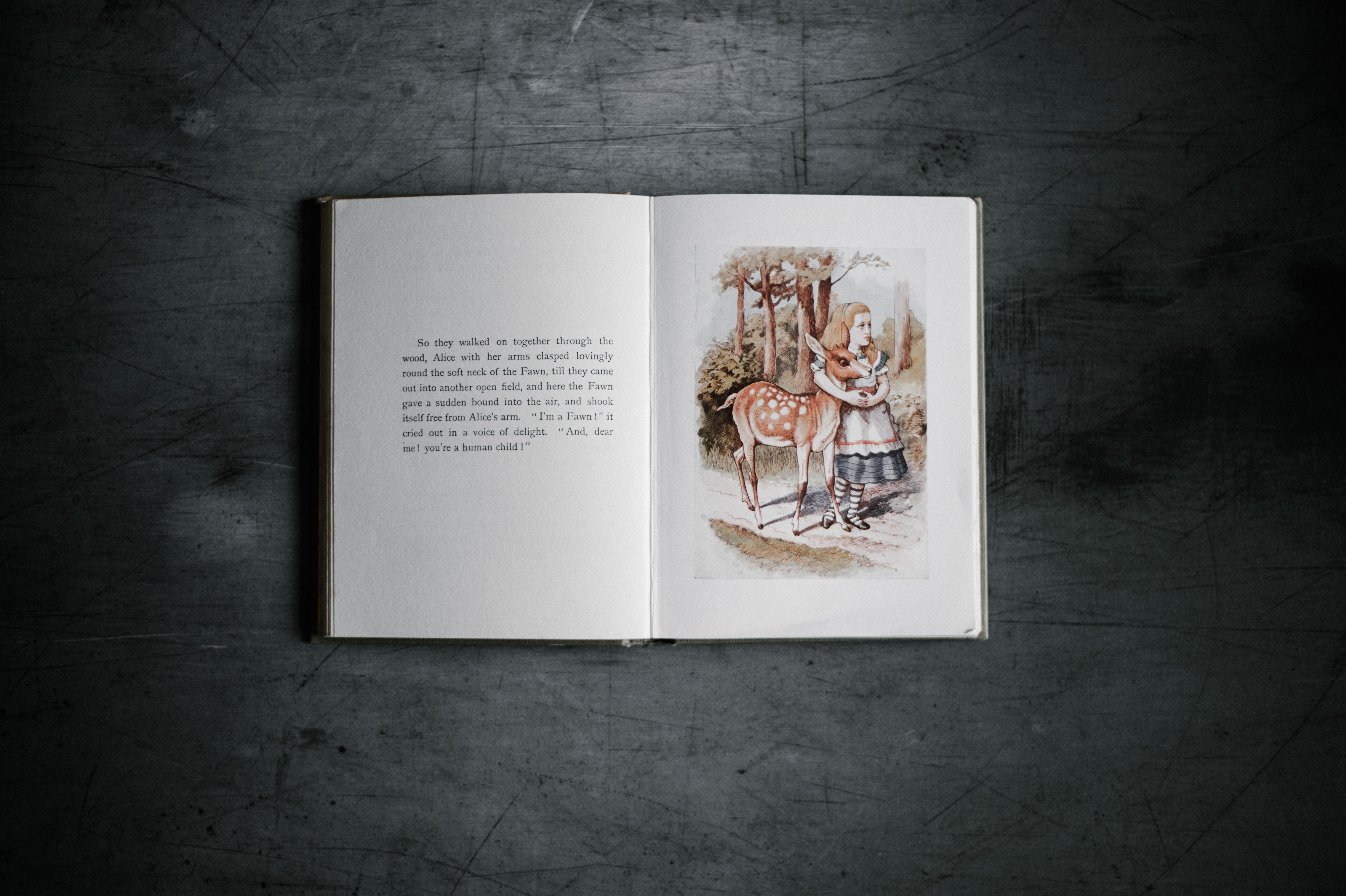

Puffy sleeves, a blue frock, and a white pinafore — it’s how we picture Alice. But Lewis Carroll actually ‘hated crinoline fashion.’ So much so that he made his illustrator change the look of Alice’s skirt five times in the ending scene of Through the Looking-Glass (1871).

But Carroll’s demands are also a mirror of the period itself. By the time he published his much-awaited sequel in the late-1800s, image-text relationship had transformed significantly, giving rise to the golden age of illustrations. But how did we get here?

First, There Were The Classics.

Historically, illustrations are as old as cave paintings. But they weren’t a flourishing language for children’s literature till the 19th century. Some old texts, like Aesop's Fables, had their own woodcut illustrations, and Scroll of Animals was animated by Toba Soja. However, neither were specifically drawn with children in mind. Nor were they available to the working class to begin with.

It’s why many consider The Visible World in Pictures (1658) by John Amos Comenius as the genre’s forerunner. Bound by 150 pictures illustrating everyday activities — like brewing beer and gardening — Comenius’ book took advantage of newer printing methods in engraving and etching to print illustrations that were engaging for children.

Books like this were still the exception rather than the rule. Especially since Western society saw children as ‘miniature adults,’ and didn’t think their reading material warranted a separate illustrated genre. The Games and Pleasures of Childhood (1657) even shows how ingrained this notion was, with children’s bodies drawn in a bizarre adult-like form.

The 18th Century Revolution: From Philosophers to Printers

It was only after philosophers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote about childhood as an altogether separate stage in life; that ideas of playfulness, naivety, and curiosity began to spread in the West. By then, the industry had its own revolution too.

Innovations in printing — from engraving to woodcutting, etching, and aquatinting — began giving 18th-century publishers more freedom to play with visuals. One such publisher was John Newbery. Based in London, Newbery’s catalogue produced a wide range of woodcut illustrations for children’s books like the famous History of Little Goody Two Shoes (1765), one of the first marketed as entertainment. In the late-eighteenth century, the growing market for children's toys also resulted in a new mania — movable books.

Known as a kind of pop-up book, movables flooded shops everywhere and became a popular form of children’s entertainment. With titles like Little Fanny (1810) — the first paper doll book — children could now toy with 7 cut-out figures, one moveable head, and four exciting hats. Such novelty books were so big that Lothar Meggendorfer, a German illustrator, made as many as 200 movables. His best work, Internationaler Zirkus (1889), revealed six three-dimensional circus acts, which could be seen individually or in entirety, all by the pull of a tab.

This continued till World War I, after which movable books were out of fashion.

The 19th Century Finale

Aside from movables, other changes were also brewing during the 19th century. Instead of being mere delight or decor, images now started to be seen as powerful storytelling vehicles. And in some cases, these were considered as important as the text itself.

So much so that by the mid-1800s, illustrators could, possibly for the first time, become famous doing so. John Tenniel, who did Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1866), is one of the most successful examples. Another illustrator from the time, Randolph Caldecott, became the first to turn away from black and white illustrations and with the help of a printing firm, popularized colour woodblock printing. Writing about his legacy, Maurice Sendak, the most honoured children's book artist said:

"Caldecott's work heralds the beginning of the modern picture book. He devised an ingenious juxtaposition of picture and word, a counterpoint that never happened before. Words are left out -- but the picture says it. Pictures are left out -- but the words say it."

The real icing, of course, for illustrators like Caldecott was a growing middle-class, more eager than ever to buy children’s books. In the later centuries, the 20th and 21st, illustrations became an omnipresent part of childhood. From sub-genres to artistic movements, newer styles and mediums, the text-image relationship diversified into the visual world we live in today.

Just take every Alice that has been inked since. Whether it's her boyish look in the 1920s, being Disney’s silver-screen heroine in the 1950s, or wearing a hot pink minidress in the 1970s. Illustrations have always had the ability to create new storylines, a world within a world.

So much so that it is hard to imagine a childhood without them.

With MerlinWand’s collection, your child can now experience the magic of illustrations firsthand. Personalize an original storybook where your child can be their own hero, choose their avatar, gender, and even pick their very own storyline!

Get your full-length illustrated story now with MerlinWand.

You have no items in wishlist.

We will send you an email to reset your password.

| Title |

|---|

| Price |

| Add to cart |

| Type |

| Vendor |